Adaptation Task Navigator

Decision trees for choosing tasks and methods

While there is agreement in the literature on the four general tasks of the adaptation learning cycle, there is little agreement how these broad tasks are broken down into more specific tasks and on which methods are applicable for addressing these. At each stage, usually a sequence of specific tasks needs to be addressed. The key challenge in the assessment of VIA and the implementation of adaptation actions is to decide which sequence of tasks to address and which methods to use for addressing these tasks.

Furthermore, there is no predefined sequence of task. Similarly to the general adaptation learning cycle, tasks are identified and methods applied iteratively. Based on the current knowledge of the adaptation situation, an initial task is formulated, methods to address it are applied, new insights about the situation are gained, which in turn lead to the formulation of a new task (see Figure 1-2).

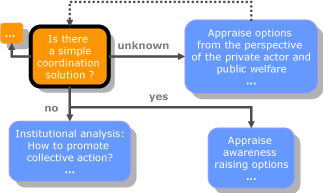

This guidance presents decision trees to support the identification of critical tasks and methods for VIA. The nodes in the decision tree embody criteria, described below, for identifying critical tasks and methods. The decision trees are presented in diagrams in which decision nodes on characteristics of the adaptation situation are represented by orange nodes. The critical tasks are represented by blue nodes.

It must be noted that the arrows are intended to show a rough indication of the critical task. In many cases, it may not be possible to provide a definitive answer in regards to the sequence of critical tasks. For example, the greater amount of resources required to carry out impact analysis imply that resource constraints indicate that capacity analysis is appropriate. This guidance does not, however, prescribe the precise threshold of resources where capacity analysis should be carried out instead of impact analysis, rather it provides an explicit set of criteria for making these choices.

Finally, it is important to note that the decision trees are accompanied by an explanatory text, which walks the reader through each node in a decision tree, and the implications of this node for the identification of the critical task and methods.

Figure 1-2: Sample decision tree. Decision nodes on characteristics of the adaptation situation

are represented by orange nodes, while critical tasks are represented by blue nodes.

Three sets of criteria are relevant for identifying critical tasks and selecting methods appropriate for addressing them. The main set of criteria are the characteristics of the adaptation situation, which will be described in more detail below. These describe the empirical conditions that must be met by the adaptation situation in order to meaningfully apply an approach or method. For example, an institution-analytical approach is only applicable to assessing vulnerabilities and impacts if the adaptation situation is such that many interdependent actors are facing various decisions. As a further example, the method of cost-benefit analysis is only applicable if the adaptation situation consists of a task in which one actor facing a decision in which outcomes can all be expressed in one metric (money).

For some tasks, the empirical setting will not uniquely determine which method should be applied, because available tasks and methods differ with respect to their underlying theoretical assumptions, which are independent from the empirical characteristics of an AS. These assumptions may be based on, for instance, the assumptions underlying a scientific discipline or school of thought or particular computational model at hand. For example, certain methods that analyse and predict the consequences of individual behaviour are based on socio-psychological theory, which links cognitive variables to the behaviour of an adapting actor. This cause-effect relationship between variables and outcomes is a theoretical assumption determined by the analyst.

Alternative methods employing assumptions of utility maximisation could be applied to the same task. A further example would be an analyst's choice between applying an impact model in which adaptation occurs, as opposed to one in which no adaptation occurs. The criteria for selecting between these alternatives is not based on the adaptation situation. For example, selecting an impact assessment method often involves the theoretical choice about how to represent autonomous adaptation, e.g. "no adaptation", "clairvoyant adaptation", etc. (F¨ssel and Klein, 2006).

A third set of criteria is pragmatic criteria associated with the analyst carrying out the work. Many of the methods require expert knowledge and the skills or expertise of the analyst is thus relevant for choosing appropriate methods. Furthermore, the resources available are relevant in that they also constrain the application of methods. In particular some of the computational and empirical methods require substantial resources to be committed. This might be a relevant in terms of considering the costs of generating new information, versus the disadvantages of acting on incomplete information. As this is a fundamental decision making problem, we cannot aim to provide definite prescriptions on these kind of choices. Finally, the scope of the assessment or the terms of references often constrain the tasks that may be addressed and the methods considered to be relevant. Here, this third set of criteria has not been used in building the decision trees in order to provide guidance based on the best available knowledge from VIA research and adaptation practice.