“What we call the eternal ice of Antarctica unfortunately turns out not to be eternal at all,” says Johannes Feldmann, lead author of the study to be published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). “Once the ice masses get perturbed, which is what is happening today, they respond in a non-linear way: there is a relatively sudden breakdown of stability after a long period during which little change can be found.”

“A few decades can kickstart change going on for millennia”

This is what is expressed by the concept of tipping elements: pushed too far, they fall over into another state. This also applies to, for instance, the Amazon rainforest, and the Indian Monsoon system. In parts of Antarctica, the natural ice-flow into the ocean would substantially and permanently increase.

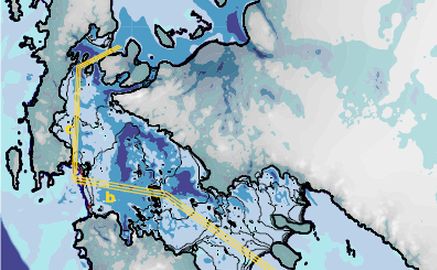

Ocean warming is slowly melting the ice shelves from beneath, those floating extensions of the land ice. Large portions of the West Antarctic ice sheet are grounded on bedrock below sea level and generally slope downwards in an inland direction. Ice loss can make the grounding line retreat, thereby exposing more and more ice to the slightly warmer ocean water – further accelerating the retreat.

“In our simulations 60 years of melting at the presently observed rate are enough to launch a process which is then unstoppable and goes on for thousands of years,” Feldmann says. This would eventually yield at least 3 meters of sea-level rise. “This certainly is a long process,” Feldmann says. “But it’s likely starting right now.”

The greenhouse-gas emission factor

“So far we lack sufficient evidence to tell whether or not the Amundsen ice destabilization is due to greenhouse gases and the resulting global warming,” says co-author and IPCC sea-level expert Anders Levermann, also from the Potsdam Institute. “But it is clear that further greenhouse-gas emission will heighten the risk of an ice collapse in West Antarctica and more unstoppable sea-level rise.”

“That is not something we have to be afraid of, because it develops slowly,” concludes Levermann. “But it might be something to worry about, because it would destroy our future heritage by consuming the cities we live in – unless we reduce carbon emission quickly.”

Article: Feldmann, J., Levermann, A. (2015): Collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet after local destabilization of the Amundsen Basin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS, Online Early Edition) [DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1512482112]

Weblink to the article: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1512482112

For further information please contact:

PIK press office

Phone: +49 331 288 25 07

E-Mail: press@pik-potsdam.de

Twitter: @PIK_Climate