“Surprisingly, oceanic acidification does counteract climate change to some extent, but with dramatic ecological consequences”, says John Schellnhuber, Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK). Matthias Hofmann, also from PIK, and Schellnhuber investigated how unabated emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) could affect the metabolism of the world’s oceans during this millennium.

In the current edition of the journal “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” the authors describe three major concomitant effects of acidification: the growth of calcifying organisms is hampered, which reduces the rise of atmospheric concentration of CO2 as a negative feedback – stabilizing climate. That means the attenuating effect increases with the rise of the concentration. The second major effect is a positive feedback, aggravating the increase in CO2 concentration: because calcification is reduced, less carbon is transported towards the sea bed by marine snow. However, this effect is weaker than the negative feedback. The third, and most pronounced, effect is the depletion of oxygen at intermediate depths, because more organic matter is oxidized there.

“We have, for the first time, investigated the manifold impacts of acidification on the oceans using a complex biogeochemical model,” says the first author, Matthias Hofmann. The researchers started out from the so-called business-as-usual scenario A1FI used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, with rising emissions of CO2 throughout the 21st century. They assumed the emissions would decrease to zero subsequently until the year 2200 and remain at zero for the rest of the millennium. In total, about 15 billion tons of CO2 would be released to the atmosphere following this scenario. The concentration in the air would rise to 1750 parts per million (ppm) in 2200 as compared to approximately 380 ppm today. By the end of the millennium it would drop again to 1400 ppm.

The calculations show that, under these assumptions, sea water takes up more CO2. Molecules of water and CO2 form carbonic acid, changing the medium to a more acidic, less alkaline state. Following the scenario, the globally averaged sea surface pH value would drop from 8.15 to 7.45 in 2200, rebouncing to a value of 7.6 in the year 3000. The value would remain alkaline, but it would be shifted towards more acidic conditions. This reduces the availability of building material for the calcium carbonate skeletons of organisms such as corals, coccolithophorides, and foraminifers. And because calcification by marine organisms involves CO2 production, a smaller amount of this gas is released to the atmosphere when calcification is reduced.

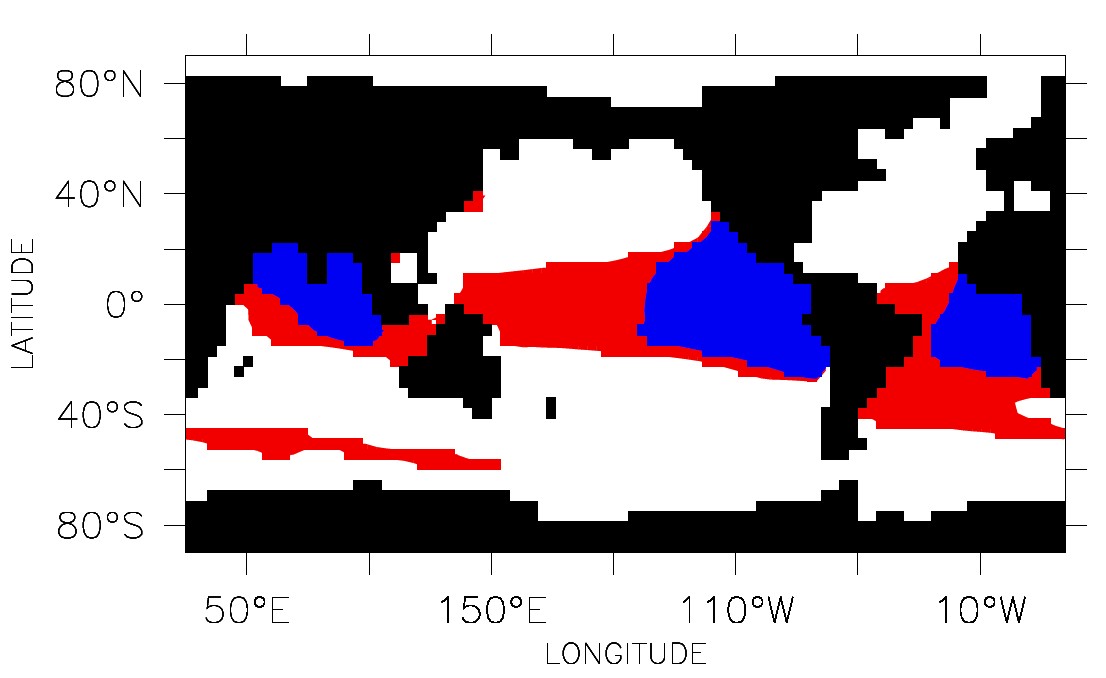

However, the skeletons of calcifying organisms act as ballast for the transport of organic carbon from the sea surface towards the deep ocean. There will be less carbon transport if the flux of mineral ballast declines, entailing a weakening of the biological carbon pump. This leads to an accumulation of organic matter in the upper water body, where it is oxidized. Oxygen could be depleted almost completely at intermediate depths from 200 to 800 metres. Because hypoxia exerts stress on macroorganisms such as fish, it is likely that this process will provoke an increase of their mortality. Hofmann and Schellnhuber conclude that oxygen holes will expand dramatically as acidification progresses. This would deteriorate the habitats of many aquatic communities severely.

Article: M. Hofmann, H.J. Schellnhuber: Oceanic acidification affects marine carbon pump

and triggers extended marine oxygen holes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

On the Web:

German Advisory Council on Global Change: Ocean Acidification

For further information please contact the PIK press office:

Phone: +49 331 288 25 07

E-mail: press@pik-potsdam.de